Bitcoin

Here’s why the Fed is pivotal to Bitcoin’s rise

Bitcoin is worth much more than what it is today. That’s not a rhetorical statement; in fact, it’s a practical one. If the metric you’re measuring Bitcoin against is potentially infinite, then to put a finite value of $10,600 on a cryptocurrency which has a fixed supply doesn’t make sense.

Every fiat currency can be supplied to the extent deemed fit by its central bank, parliament, or head of government. There’s really no end. But there is a need, and this ‘need’ is playing out as we speak.

Take the U.S dollar, the world’s go-to reserve currency, and the most widely used metric to measure the price of Bitcoin. The U.S dollar is printed by the Federal Reserve, a central bank that has a very straightforward playbook, according to a recent report by Ecoinometrics.

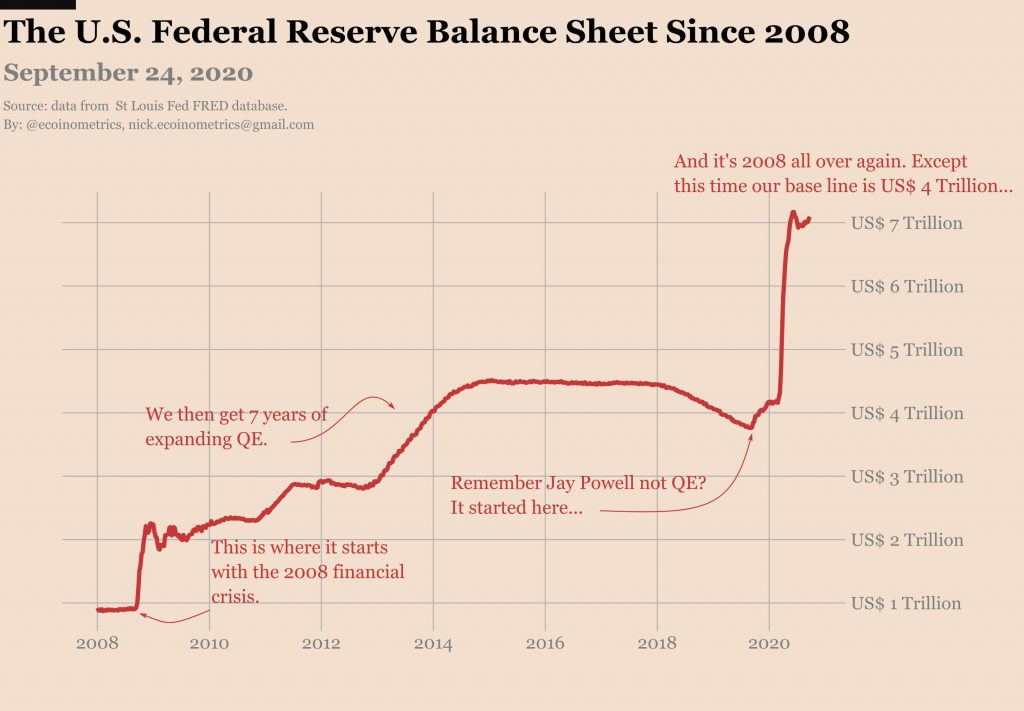

Everything is fine and dandy until a crisis hits the country. Once the crisis has shaved a couple billion off the domestic stock market, the Fed gets into action. A massive amount of liquidity or fresh dollars are supplied into the economy in order to stimulate demand and jerk the market back to the point it was before the crisis.

Between 2008 to 2018, the total assets’ value on the Fed’s balance sheet grew to $4.5 trillion. For context, that’s 441 million Bitcoin as per today’s prices, but once again, that’s an impossible number of Bitcoin. Why? Because there can only be a total of 21 million Bitcoin. A bank or a company simply cannot pump more into the market, even if there is a global pandemic killing millions.

Once the crisis passes, the Fed will wait once again for things to stabilize before the ring in its second liquidity program. While the first was mainly through stimulating demand, the second is through stimulating supply by quantitative easing. This process, despite being denied in theory, is haphazard in action, with the Federal Reserve pumping billions into the economy in weeks by acting through its commercial banks.

US 10-year Treasury Yield | Source: Ecoinometrics

The effect of this expansion, against Bitcoin’s price, has been quite clear in the yield of the government’s favorite asset, the treasury bonds. In the early 1990s, the treasury yields, or the interest rate on these government-backed long-term (30-year) bonds, was in excess of 9 percent. Now, they are close to 0 percent. This can be seen inversely as the rate of expansion of the economy. With every new printing run, the yield is bound to drop and any fixed asset measured against it is bound to rise. Sound familiar?