Bitcoin

Bitcoin sextortions: How and Why so many have fallen victim

Sextortion is a fairly new word. Much like ‘selfies’ and ‘memes’ sextortion is an addition to the English language because of the growth of technology. But unlike a self-portrait of a ‘duckface’ or an ill-pronounced word depicting pictorial humor, sextortion is far more nefarious, and not in the least bit funny.

Sexual extortion involves withholding sensitive information of scores of people in compromising positions, threatening to make it public if a ransom is not paid. While the modus operandi of the crime is traditional, the mode of payment is not. Criminals in the sextortion racket prefer one form of payment and one form of payment only – Bitcoin.

Changing direction

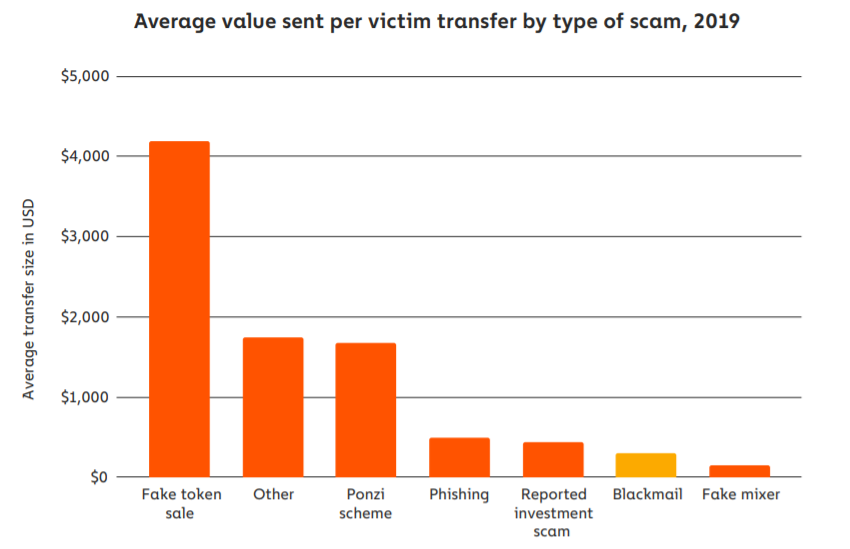

Classified under ‘Blackmail’ scams, because of the medium employed, a report by Chainalysis, classified it as the sixth most potent cryptocurrency scam, based on average transfer size, behind fraudulent coin offerings, phishing scams and ponzi schemes.

The 2020 State of Crypto Crime report | Source: Chainalysis

The report further highlighted that sextortion in the cryptocurrency world had a “low success rate,” given the low number of successful payments to the high number of scams sent.

Researchers at Cornell who studied sextortion campaigns for almost a year concluded that “one single entity,” is controlling the “the majority of the sextortion campaigns,” which generated a whopping $1.3 million in stolen Bitcoin. Their conclusion sounded alarm bells for the cryptocurrency community at large,

“We conclude that sextortion spamming is a lucrative business and spammers will likely continue to send bulk emails that try to extort money through cryptocurrencies.”

Further, the Chainalysis report, looking at the sextortion scams from the perspective of ‘spam campaigns’ stated that sextortion is “one of the most profitable,” given the low infrastructural cost to the payout possibility.

Deeper than it looks

From September 2019 to January 2020, Sophos a software security firm produced a report detailing how criminals use spam messages in these sextortion campaigns and funnel millions from victims.

Sextortion to spam variability | Source: Sophos sextortion report

Timing

While sextortion can be categorized as spams, its proportion varies. The report stated that for the entire period of study only 4.23 percent of all spam emails can be attributed to sextortion, but on certain days, the proportion jumped to 20 percent. The sextortion email traffic increased during autumn and peaked in the winter months. Between 24 to 26 December, there was an isolated spike, with the report stating that the scammers “prefer to send their messages [sextortion emails] when their targets might not be at work.”

Spread

The source of the emails was spread out, as the scammers used botnets from “compromised personal computers,” to email targets. Surprisingly, Vietnam had the highest single share at 7 percent of total routing. Sophos noted that the messaging was “sophisticated,”

” Some of the messages demonstrated some new methods being used by sophisticated spammers to evade filtering software.”

Conceal

Given the scattershot approach of the targeting and the concealed nature of the messaging, the scammers underlay the emails with a few gaps in the code, for customization. In order to evade text detection, the report found “image-based obfuscation,” which included the breaking up of strings and the use of non-ASCII characters, invisible white garbage to “break up the message text.

Kill the messenger

Messaging is the crux of sextortion scams. In the body of the spam/sextortion email the scammer must mislead the victims that videos or pictures of them engaging in ‘private acts’ has been captured, and will be shared it certain payment is not made. Given that many sextortion cases are “spams,” the threats are hollow, and scammers are bluffing.

However, they employ a host of reasoning to dupe the targets into believing that their system was compromised. The aforementioned Cornell research listed 15 “distinctive features,” of sextortion campaigns.

Features of sextortion campaign | Source: Sextortion in the Bitcoin Ecosystem, report

Here’s another picture of the exact message crafted for a sextortion scam. The scammer states that they placed a “malware,” on a porn website that the victim visited, the web-browser acted as a “Remote Desktop,” allowing the scammer to access the display screen and webcam. Further, contact information was stolen to leak the information to sensitive parties.

Later, the scammer threatens the victim with the leakage of a split-screen showing said “porn,” with the target engaging in “nasty things.” The ransom of $750 [in this case] is presented with a [redacted] Bitcoin address.

Notice the general language of the email, with no mention of the victim’s name, website(s) visited, specific type of content viewed, or date of breach. As mentioned earlier such messages are sent to several unsuspecting email IDs.

Sextortion message example | Source: Sophos sextortion report

Paper trails

Once the messaging is established, then comes the payment. Most victims call the scammers’ bluff and do not send the Bitcoin ransom. In the Sophos 5-month long study, only 328 wallet addresses received payments, from a total of 50,000 unique Bitcoin wallet addresses in the intercepted emails. The report stated, “only a half a percent [0.65 percent] of each message volley convinced recipients to pay.”

The 328 addresses that received payment saw a grand total of 96 Bitcoins generated, which amounts to $864,000 by the press time conversion rate. However, only 81 percent of the wallets received payment within the period of the sextortion campaign, with the remaining amount attributed to previous transfers and not a part of the scam. Hence, the active 261 addresses during the period generated 50.98 Bitcoins, or $459,000. Each of the 261 active addresses received on average ~$1,800.

Movement from and between these addresses was common. The scammers “regularly cycled” through the wallet for every campaign, with the average lifespan of each address being 2.6 days before they disappeared from the overall spam campaign. But if an address was “successful,” i.e. if it received payment, its lifetime was extended to an average of 15 days.

Follow the coin

Next comes blockchain analytics to track how the Bitcoin was transferred and liquidated. For this, Sophos used the specialties of blockchain analytics firm CipherTrace.

Out of the 328 active addresses, 12 were “connected” to online exchanges and other wallet services. The report added that CipherTrace had categorized many of these exchanges as “high risk” and hence “making them well-suited as cryptocurrency laundering points for criminals.” Speaking to AMBCrypto, Dave Jevans the CEO of CipherTrace stated that exchanges are “high risk” if they have “poor or non-existent Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures” and are determined to “facilitate criminal activities.”

Once the sextorted funds were dumped in these exchanges, further tracking was not possible. The report read,

“These previously attributed addresses were not used in further tracing the flow of funds from the campaigns, because exchanges often combine customer funds together in their deposit pool—making it untenable to track specific blockchain transactions further.”

However, 476 “output transactions” were produced, and among the recurring destinations were some big-name spot and P2P exchanges. The highest source of “output transactions” was with Binance, at around 14.76 percent or 70 transactions, followed by LocalBitcoins, with 10 percent or 48 transactions. The remaining transactions were distributed to CoinPayments, wallets within the sextortion campaign and “private non-hosted wallets.”

In terms of the 50.98 BTC siphoned [within the period of the scam], 44 percent or 22.43 BTC went to exchanges, a separate 15 percent or 7.64 BTC went to “high risk” exchanges, 11 percent or 5.6 BTC to private wallets, 10 percent or 5.09 BTC to carding sites, and the rest to gateways, gambling sites, Bitcoin mixers and the Dark Markets.

Bitcoin dissemination from sextortion wallets | Source: Sophos sextortion report

Exchanges in most criminal transactions of this sort are unconsenting participants. “Exchanges are the primary on and off ramps,” said Kim Grauer, head of research at Chainalysis, a blockchain research firm. She added that in 2019, over $2.8 billion in Bitcoin was traced from “criminal entities” to exchanges.

The report pointed out, exchanges do not know where the money is coming from and hence are “unknowing participants in these deposits.” In the event of a hack, where there is a breach of exchange and customer wallets, from which funds are siphoned to the scammers’, the wallets on both ends i.e. the victims’ and the scammers’ are flagged. Any movement of the funds from the scammers’ wallets to third-party exchanges for liquidation is traced. However, in the case of sextortion there is neither an obligation nor a structured tracking given the distribution of the victims.

Once an exchange is made aware of the sextortion link, they can intervene. Jevans told AMBCrypto that CipherTrace “enables exchanges to flag sextortion cases if they are linked to the criminal.” However, there is no enforcement of the same until the law comes in,

“There is no obligation to do anything with sextortion until there is a legal complaint.”

Finally, there’s the question of longevity – how long did the funds sit in the addresses? While CipherTrace did not provide the pace at which the funds were liquidated i.e. sold for cash, they did reveal the “lifespan” of the wallets.

Of the 328 addresses, 13 had no “outbound transactions.” Given the fact that the 305 wallets had an average lifespan of 32.28 days, the report stated “whoever was behind the wallets did not let their cryptocurrency spoils sit for long.” Removing the 9 wallet outliers which existed for 200 days, over 50 percent of the remaining 296 addresses had a shorter lifespan of 19.93 days. Of these 296 addresses, 143 addresses or had just two transactions – one input and one output, putting their lifespan at around 8 days.

Sextortion BTC addresses lifespan

Dark road ahead

Beyond the exchanges and the other avenues of deposit of the sextorted funds, tracking remains foggy. The Sophos report stated that 20 of the 328 addresses had IP associated addresses but linked to VPNs or TOR exit nodes, hence stifling geo-location tracking.

The scammers operate on a large scale hit-or-miss approach, sending a broadcast of threatening emails to vulnerable victims. While many do not respond, a significant portion does, which is enough for the scammers to generate millions in Bitcoin. However, the siphoning of Bitcoins is not the end of the campaign, it is perhaps the start of it. CipherTrace CEO Jevans concluded, the criminals engaged in sextortion are likely those that conduct large scale scams in the cryptocurrency world and beyond. He said,

“Sextortion cases are often linked to the same criminals who perpetrate ransomware and phishing. It is often the same infrastructure used for cashing out the funds, as well as for sending the emails.”